© UK Photo And Social History Archive

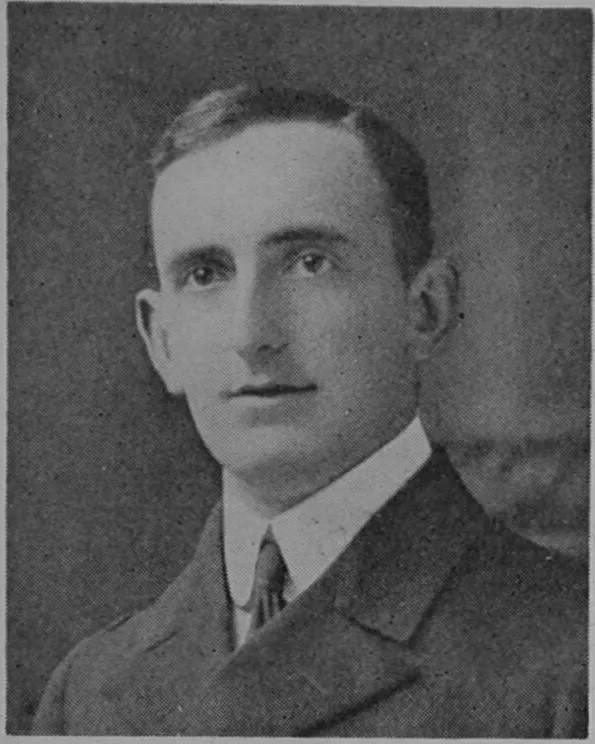

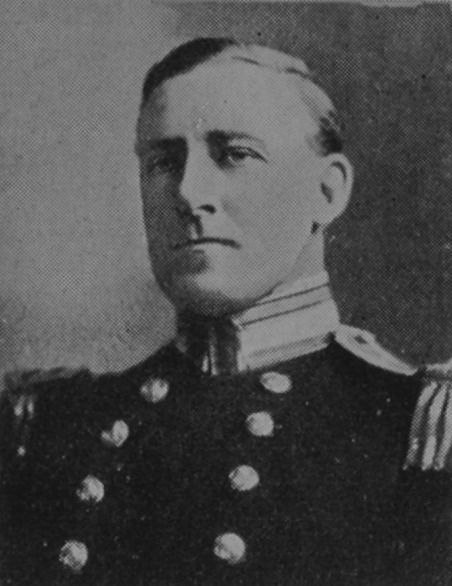

After much delay, today I finally completed a draft of the last chapter of my next book. This will be a biography of Commander Francis Goodhart, told alongside that of the major warship which he sank, the armoured cruiser SMS Prinz Adalbert.

By coincidence today is also the day of an annual service held at Faslane Cemetery to commemorate those lost on HMS K.13, which sank on her acceptance trials in the Gareloch on 29 January 1917. Goodhart lost his life the next day during a daring attempt to hasten aid for those trapped in the boat.

Goodhart had been appointed to command K.14, which was still under construction on the Clyde. He had been invited along to the trial as a guest by his friend, Godfrey Herbert, the captain of K.13.

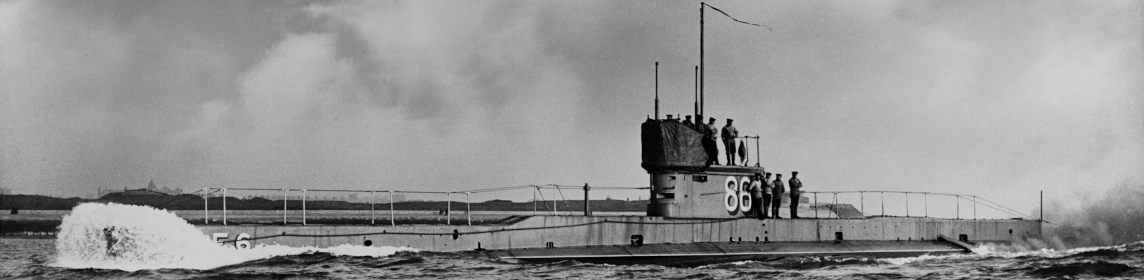

The K class submarines were a technological marvel. Their design called for a submarine capable of a surface speed of 24 knots to operate in conjunction with the main battle fleet. Since contemporary diesel engines were not capable of these speeds, this meant using oil fired boilers to power steam turbine engines. The result was a submarine that doubled the size of those in service. A whole range of new systems were introduced. Two funnels and four large boiler room vents were needed to feed air to the boilers and take away the combustion products. On diving new hydraulic telemotor powered systems automatically retracted the funnels into the superstructure and covered the vents and funnel trunking.

The layout can be seen in this plate, taken from an Admiralty technical history published in 1921:

It has been a fascinating task piecing together the events from the archive material, eyewitness accounts and memoirs that deal with them. Reconciling different accounts is not straightforward and it is important to understand each writer’s perspective, potential biases and the amount of time that elapsed before they recorded their account. It is also important to keep an open mind and not jump to conclusions. The tale will be told in full in the chapter I have just finished drafting, but the key events are summarised below.

The immediate cause of K.13 losing control and plunging to the bottom of the Gareloch on her final dive was without doubt the fact that the boiler room mushroom vents had not been closed, based on the testimony of survivors to the Court of Inquiry held shortly after the disaster. The position of the vents was also confirmed by the salvage divers. Many accounts incorrectly assume that the loss was related to the complexity of the funnel mechanism, but this played no part in the sinking and was a separate system.

The aft section of the boat flooded almost immediately; 31 men lost their lives. In the forward section 48 men were trapped. Poor communication meant that after nearly a day on the bottom there appeared to be little progress with rescue efforts from those at the surface.

Goodhart and Herbert hatched a plan to get to the surface to ensure that the salvage efforts above quickly focussed on the essential needs of the trapped men. This meant Goodhart attempting a highly dangerous ascent via the conning tower and the wheelhouse which surrounded it. Herbert would assist, after which he planned to return to the control room of K.13. Compressed air would be used to assist the ascent, from a depth of around 20m, without any form of escape apparatus.

Goodhart was caught in the stream of compressed air when he left the conning tower and was killed when his head struck the roof of the wheelhouse. Herbert was sucked out of the conning tower after him, but managed to get out of the wheelhouse and reach the surface. He played a key role in ensuring that the remaining 46 men were kept alive until they were rescued.

Goodhart’s sacrifice was recognised with the posthumous award of an Albert Medal in Gold; the highest award for bravery when not engaged in military action. It is equivalent to the modern George Cross.

Petty Officer Moth, one of those rescued, described Goodhart and Herbert as: ‘Two of the bravest men it is possible to meet.’

Goodhart died in the finest tradition of the Royal Navy, not hesitating to be the one to risk his life for his shipmates. As one of the outstanding allied submariners of the Great War, a biography is long overdue.